The film includes excerpts from Jonas Kaufmann’s album recording sessions with soprano Julia Kleiter, the Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester Berlin and conductor Jochen Rieder in the Funkhaus Berlin. Interviewees include Yvonne Kálmán (daughter of composer Emmerich Kálmán), Marta Eggerth, and Clarissa Stolz-Henry (the foster-daughter of Robert Stolz). Archival film footage is also interwoven throughout the documentary, with selections from various operetta movies („Ein Lied geht um die Welt“, „Ich liebe alle Frauen“), radio-documents, hit records by Richard Tauber, Joseph Schmidt, Helge Rosvaente, Jan Kiepura, and historic film news bulletins.

“Freunde, das Leben ist lebenswert!” – Friends, life is well worth living!”

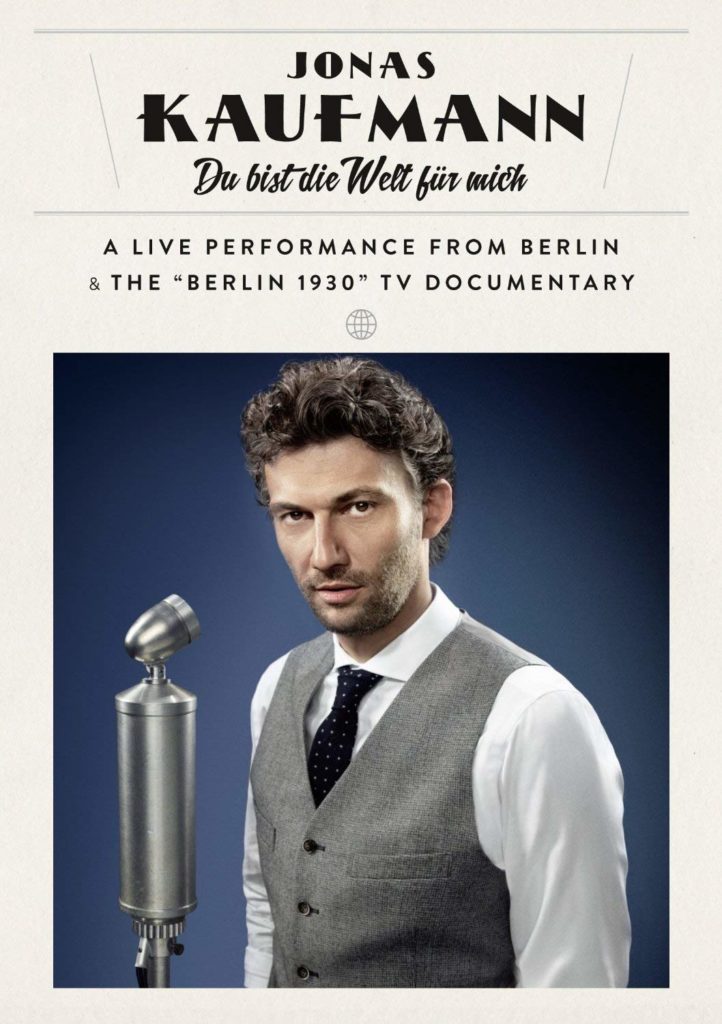

A clarion-voiced Jonas Kaufmann addressed these words of encouragement to an audience of twenty thousand at a concert in Berlin’s Waldbühne in August 2011. It was on that occasion that the idea for the present programme was conceived. Why should songs such as “Yours Is My Heart Alone” and “You Mean the World to Me” be no more than encores? Why not make them and other perennial favourites the main programme, especially when a singer is as fond of this music and sings it as well as Jonas Kaufmann?

From the outset it was clear that this would be no hit parade featuring famous numbers from operettas but would reflect a coherent concept made up not of insipid arrangements but of the original versions of these songs. The vast field that stretches from Die Fledermaus to Die Blume von Hawaii was reduced in scope to the years between 1925 and 1933, from hits which Franz Lehár had written for Richard Tauber to the heyday of the popular numbers taken from the early talkies. In short, the period covered extends from the Roaring Twenties to the expulsion and exile of all those composers, lyricists and singers who had substantially influenced the medium. Invited to draw up the programme, I immediately plunged into one of the most exciting chapters in the whole history of German music and culture.

The scene is Berlin. It is here that our story begins on 30 January 1926 at the Deutsches Künstlertheater, where Franz Lehár’s operetta Paganini had just received its German première, an event that the composer had viewed in advance with a certain trepidation, for the piece had proved a flop when staged in Vienna three months earlier. “You must sing in Berlin,” Lehár had urged his friend, Richard Tauber, “a second failure is unthinkable.” In the wake of the work’s failure in Vienna, the theatre manager in Berlin had had second thoughts and wanted to renege on the contract he had signed with the composer, but Lehár took him to court and following the judge’s verdict the director almost literally had success foisted upon him: thanks to Tauberthe piece was a runaway success in Berlin. Time and again the audience demanded a repeat of “Gern hab ich die Frau’n geküsst” – widely known in English as “Girls Were Made to Love and Kiss” –, which Tauber sang no fewer than five times on the opening night alone. Lehár described the occasion as his artistic rebirth, while for Tauber it marked his transition from an acclaimed opera singer to a matinee idol. Together they were invincible. Paganini was followed in 1927 by Der Zarewitsch, in 1928 by Friederike (with Käthe Dorsch in the title role and Tauber as Goethe), in 1929 by Das Land des Lächelns (The Land of Smiles), in 1934 by Schön ist die Welt (The World is Beautiful) and in 1934 by Giuditta, the very first operetta to be premièred at the Vienna State Opera.

The tremendous popularity that Tauber and Lehár enjoyed as a team is clear not least from the reaction of those who found such triumphs a source of suspicion and envy. The Viennese cultural critic Karl Kraus, for example, contributed a whole series of exquisitely venomous pieces to his own journal, Die Fackel, in which he inveighed against the “operetta shame of the present day”. Throughout this period Lehár’s most powerful rival was Emmerich Kálmán, who had already supplanted him in Vienna as the king of operetta, not least thanks to the help of his most important associate at this time, the singer, actor and director Hubert Marischka, who ran the Theater an der Wien, the scene of Lehár’s earlier triumphs in the Austrian capital. It was with Kálmán’s Gräfin Mariza (Countess Maritza) that Marischka enjoyed one of his greatest successes both as a director and as a singer. Onstage he was the very embodiment of an operetta beau, although on record he sounds unseductive. As a result, the tenor’s hit number from Countess Mariza, “Grüß mir mein Wien” (Say Hello to My Vienna), became internationally famous not in Marischka’s recording but in the version recorded with Tauber in Berlin, a musical symbol of the tense relations that existed between the two cities and also between Lehár and Kálmán, while at the same time encapsulating the longing for romance and gemütlich delights in economically brutal times. In the melodies of these Viennese composers and in the singing of Richard Tauber, Berliners found an emotional outlet. They could abandon themselves to their dreams, allow their feelings free rein and weep without embarrassment in the “land of smiles”.

Even those who knew the show-business scene in Berlin in all its harsh reality and who had gradually grown weary of the surfeit of sensory stimuli that it had to offer could revel in Tauber’s heartfelt singing. One such artist was Marlene Dietrich. “Now I know why Bing Crosby is such a big star and why I like his records,” she wrote from Hollywood to a friend in Berlin. “He’s learnt everything from Tauber.”

Tauber was less successful as a composer, although his operetta Der singende Traum (The Singing Dream), which opened at the Theater an der Wien on 31 August 1934 in a production by Hubert Marischka, ran for eighty-nine performances in spite of a number of malicious reviews. And the tenor solo “Du bist die Welt für mich” (You Mean the World To Me) became a timeless hit not least thanks to the recording that Tauber made seven months later, albeit as its conductor: the singer was Tauber’s greatest rival, Joseph Schmidt.

If Tauber became a pop star mainly as a result of his Lehár premières, Joseph Schmidt, who at 5’ 1’’ was simply too short of stature to enjoy a stage career, achieved popularity through the new media of radio and the talkie, becoming the favourite tenor of the new era. Millions idolized the little man with the magnificent voice that expressed a wistful sadness and tearful emotion capable of moving the hearts of all his listeners. The title song of his film “Ein Lied geht um die Welt” (My Song Goes Round the World) says it all. Like most of Schmidt’s film hits, it was written by the Vienna-born composer Hans May.

Meanwhile, another career was burgeoning in Berlin: that of the Polish tenor Jan Kiepura. Although Kiepura lacked the musical elegance of a singer like Tauber and had none of Schmidt’s wistful, heartfelt warmth of voice, he had something that Tauber lacked: high Cs in abundance. And whereas Schmidt appealed to his female listeners’ maternal instincts, Kiepura was from head to toe a singing sex symbol. Whenever he sang “Ob blond, ob braun, ich liebe alle Frauen” (Blonde or Brunette, I Love All Women) and “Heute Nacht oder nie” (Tonight or Never), even the strongest of women went weak at the knees.

If Franz Lehár was the king of operetta composers in Berlin, then Robert Stolz was soon the leading composer in the dream factory of the sound film. As had been the case with Lehár, a string of failures had driven him to Berlin, where he brought Viennese charm and conviviality to the local musical scene. Titles such as “Zwei Herzen im Dreivierteltakt” (Two Hearts in Three-Four Time), “Adieu, mein kleiner Gardeoffizier” (Goodbye, My Little Soldier), “Blonde or Brunette” and “Auf der Haide blüh’n die letzten Rosen” (On the Heath the Last Roses are Blooming) made Stolz an international celebrity. Not as well known as those hits but very charming is one song, Jonas Kaufmann chose for his programme: “Im Traum hast du mir alles erlaubt” (In My Dream You Let Me Do Everything) from the film Liebeskommando.

Like so many other Austrian artists, Stolz spent the 1920s in Berlin, experiencing the rise and fall of the Weimar Republic at first hand. When the National Socialists came to power in 1933, he returned to Austria and did what he could to subvert the political system, giving “Aryan”-sounding names to his two most brilliant lyricists, Walter Reisch and Robert Gilbert, and boasting to the National Socialists’ minister of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, that they were his “new discoveries”. Between 1933 and 1938 he divided his time between Berlin and Vienna, saving the lives of many persecuted people by hiding them in his limousine on his journeys back to Austria. Following the annexation of his native Austria, Stolz fled to Paris via Switzerland and from there to New York, where – coincidentally – he lived in exile in the same apartment block as Emmerich Kálmán. Together with his wife Yvonne (known as “Einzi”) Stolz returned to Vienna in 1946. In the following decades he became a sort of pop icon in the TV and recording business, not only as composer but also as conductor of operetta, waltzes and Viennese Music. At the age of 94 he was still recording and on tour. After recording sessions in Berlin he became ill; he died on June 27 in 1975, a few weeks before his 95th birthday.

Thomas Voigt

Translation: Stewart Spencer